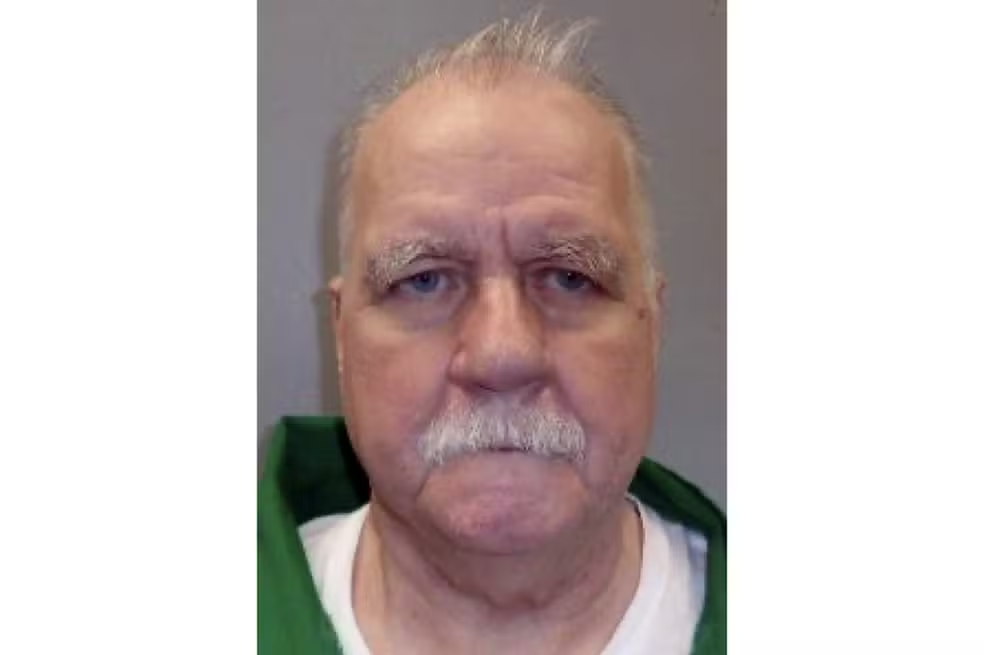

Brad Sigmon, a 67-year-old American convicted of bludgeoning his ex-girlfriend’s parents to death with a baseball bat in 2001, was executed by firing squad on the evening of March 7, 2025, in South Carolina, marking the first use of this method in the United States in nearly 15 years. The execution, carried out at 6:08 p.m. local time (8:08 p.m. Brasília) in the Broad River Correctional Institution’s death chamber in Columbia, was only the fourth firing squad execution since the reinstatement of the death penalty in the U.S. in 1976. Strapped to a metal chair with a target over his heart and a hood covering his face, Sigmon faced three volunteer shooters armed with rifles loaded with fragmenting bullets, dying swiftly as witnesses observed blood and a bullet hole in his left chest. Dressed entirely in black, including Crocs, he appeared calm, waving to his attorney before delivering his final words, muffled by the hood, moments before the shots rang out after a two-minute silence punctuated by deep sighs.

South Carolina, one of five U.S. states allowing firing squads alongside Mississippi, Oklahoma, Utah, and Idaho, resumed executions in 2021 after a 13-year hiatus due to a shortage of lethal injection drugs. Sigmon’s death was the state’s fifth execution since then and its first by firing squad, a method last used nationally in 2010 in Utah with Ronnie Gardner. Sigmon opted for bullets over the electric chair, which he feared would “cook him alive” with 2,000 volts, or lethal injection, citing the secrecy surrounding South Carolina’s pentobarbital and recent botched executions causing prolonged suffering. His legal team’s last-ditch efforts to delay the execution via the state Supreme Court and a clemency plea to Governor Henry McMaster failed, with both denied on March 6 and 7, respectively, sealing his fate in a process costing the state $53,000 to adapt the death chamber.

The execution drew global attention for its graphic nature and historical rarity. Of the 1,591 executions in the U.S. since 1976, only four have been by firing squad, all in Utah, underscoring the method’s scarcity. Sigmon, who killed David and Gladys Larke in Greenville County and kidnapped his ex-girlfriend at gunpoint, was witnessed by journalists, lawyers, and victims’ relatives, who saw the aftermath of the shots. His final meal—fried chicken, mashed potatoes with gravy, green beans, and cheesecake—offered a poignant contrast to the violent end, in a state that has executed 44 individuals since resuming capital punishment.

Firing squad reignites execution debate

Sigmon’s choice of the firing squad thrust a decades-old debate about execution methods back into the spotlight. South Carolina reinstated the method in 2021 via legislation signed by McMaster, prompted by dwindling supplies of lethal injection drugs after pharmaceutical companies halted sales in 2011. Among the 24 U.S. states where the death penalty remains legal, only five permit firing squads, with South Carolina now leading its modern application. The three shooters, volunteers from the Department of Corrections, fired from 15 feet away through a slit in the chamber wall, their rifles synchronized after the warden’s command.

Critics decry the method’s brutality, with witnesses noting the bloodshed and visceral impact, while proponents argue it ensures a quicker death than lethal injections, which have caused up to 20-minute agonies in South Carolina since 2021, or the electric chair, last used there in 2008. Sigmon’s execution, completed in under two minutes, contrasted with the state’s average 15-minute lethal injections, fueling discussions about what constitutes “cruel and unusual” punishment under the 8th Amendment.

Legal appeals fall short

Sigmon’s defense, led by attorney Gerald “Bo” King, fought tirelessly to postpone the execution. On March 6, they appealed to the South Carolina Supreme Court, arguing insufficient transparency about the lethal injection drug pentobarbital violated constitutional rights, but the court rejected the plea. A clemency request to Governor McMaster, emphasizing Sigmon’s remorse and Christian faith, was denied hours before the 6 p.m. deadline. A final push to the U.S. Supreme Court also failed, cementing March 7 as the execution date after a 23-year legal battle.

Brutal crime seals death sentence

Sigmon’s conviction stemmed from a savage 2001 crime in Greenville County. Enraged after David and Gladys Larke evicted him from their trailer where he lived rent-free, he stormed their home, beating them to death with a baseball bat in separate rooms. He then kidnapped his ex-girlfriend at gunpoint, firing at her as she fled but missing. A 2002 jury rejected life imprisonment, sentencing him to death for the double murder. Over 23 years on death row at Broad River, where 35 inmates await execution, Sigmon expressed regret, spending hours in prayer, though this failed to sway the courts or governor.

Human rights groups labeled the firing squad “medieval,” but victims’ families, present at the execution, found closure. The case’s brutality underpinned South Carolina’s resolve, despite global condemnation.

Timeline of South Carolina’s death penalty

Key events trace the state’s capital punishment history:

- 1976: U.S. Supreme Court reinstates death penalty after a four-year moratorium.

- 1995: South Carolina conducts its first lethal injection execution.

- 2008: Last electric chair execution in the state.

- 2010: Last U.S. firing squad execution in Utah.

- 2021: Law reinstates firing squad and sets electric chair as default.

- March 7, 2025: Sigmon executed by firing squad.

This timeline highlights the shift in methods, with firing squads reemerging after 15 years.

Execution methods spark controversy

Sigmon’s death intensified scrutiny of U.S. execution practices. Lethal injection, adopted in 1977 as a “humane” alternative to hanging and electrocution, has faced shortages since 2011, prompting states like South Carolina to revive firing squads and electric chairs. Of 1,591 executions since 1976, 1,363 used lethal injection, 163 electrocution, and four firing squads—all in Utah until now. South Carolina’s five executions since 2021 included three lethal injections marred by prolonged suffering reports, pushing the state to alternative methods.

Firing squads, historically tied to military justice and repression, are praised by some for speed—death in seconds if shots hit the heart—but condemned for their gore. The electric chair, operational since 1912 at Broad River and tested in 2024, is shunned by 80% of condemned inmates, per state data, due to its burning effects.

Witnesses describe graphic scene

South Carolina’s firing squad protocol features three shooters with live rounds, unlike Utah’s mix with one blank. Positioned 15 feet from a slit in the chamber wall, they fired at Sigmon, strapped with a target and hood, as 12 witnesses—including media and victims’ kin—watched through bulletproof glass. The shots, following a silent pause, left blood and a chest wound, described as “vivid and bloody” by observers. The $53,000 chamber retrofit in 2022 ensured precision, but the visceral aftermath stunned attendees.

Sigmon’s final meal of fried chicken and sides, served the previous day, preceded a swift execution lasting under three minutes, with his last sighs echoing in the chamber.

Other states eye firing squads

Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah also permit firing squads, while Idaho approved them in 2025 as a fallback if lethal injections fail. Of 35 U.S. executions in 2024, 90% used lethal injection, but dwindling pentobarbital stocks spurred alternatives like nitrogen hypoxia, debuted in Alabama, and firing squads. South Carolina defaults to the electric chair since 2021, but Sigmon’s choice highlighted firing squads’ resurgence, driven by his rejection of other methods’ perceived cruelty.

This shift reflects a broader impasse: with 24 states retaining the death penalty, finding effective, legal methods remains divisive, though 60% of Americans back it for murder, per 2024 polls.

Global outcry follows execution

Sigmon’s execution, South Carolina’s fifth since 2021, sparked international backlash, with human rights groups branding firing squads “barbaric.” Of 50 countries with capital punishment, 20 use firing squads, including Indonesia, which executed two Brazilians in 2015. In the U.S., the method’s rarity contrasts with Sigmon’s choice, rooted in fears of prolonged suffering from electrocution or injection. South Carolina’s 44 executions since 1976 cost an average of $70,000 each, with Sigmon’s requiring $53,000 in chamber upgrades.

His death, marked by muffled final words under a hood, leaves a legacy in U.S. capital punishment history as the 35 remaining death row inmates in the state await their fates.

Brad Sigmon, a 67-year-old American convicted of bludgeoning his ex-girlfriend’s parents to death with a baseball bat in 2001, was executed by firing squad on the evening of March 7, 2025, in South Carolina, marking the first use of this method in the United States in nearly 15 years. The execution, carried out at 6:08 p.m. local time (8:08 p.m. Brasília) in the Broad River Correctional Institution’s death chamber in Columbia, was only the fourth firing squad execution since the reinstatement of the death penalty in the U.S. in 1976. Strapped to a metal chair with a target over his heart and a hood covering his face, Sigmon faced three volunteer shooters armed with rifles loaded with fragmenting bullets, dying swiftly as witnesses observed blood and a bullet hole in his left chest. Dressed entirely in black, including Crocs, he appeared calm, waving to his attorney before delivering his final words, muffled by the hood, moments before the shots rang out after a two-minute silence punctuated by deep sighs.

South Carolina, one of five U.S. states allowing firing squads alongside Mississippi, Oklahoma, Utah, and Idaho, resumed executions in 2021 after a 13-year hiatus due to a shortage of lethal injection drugs. Sigmon’s death was the state’s fifth execution since then and its first by firing squad, a method last used nationally in 2010 in Utah with Ronnie Gardner. Sigmon opted for bullets over the electric chair, which he feared would “cook him alive” with 2,000 volts, or lethal injection, citing the secrecy surrounding South Carolina’s pentobarbital and recent botched executions causing prolonged suffering. His legal team’s last-ditch efforts to delay the execution via the state Supreme Court and a clemency plea to Governor Henry McMaster failed, with both denied on March 6 and 7, respectively, sealing his fate in a process costing the state $53,000 to adapt the death chamber.

The execution drew global attention for its graphic nature and historical rarity. Of the 1,591 executions in the U.S. since 1976, only four have been by firing squad, all in Utah, underscoring the method’s scarcity. Sigmon, who killed David and Gladys Larke in Greenville County and kidnapped his ex-girlfriend at gunpoint, was witnessed by journalists, lawyers, and victims’ relatives, who saw the aftermath of the shots. His final meal—fried chicken, mashed potatoes with gravy, green beans, and cheesecake—offered a poignant contrast to the violent end, in a state that has executed 44 individuals since resuming capital punishment.

Firing squad reignites execution debate

Sigmon’s choice of the firing squad thrust a decades-old debate about execution methods back into the spotlight. South Carolina reinstated the method in 2021 via legislation signed by McMaster, prompted by dwindling supplies of lethal injection drugs after pharmaceutical companies halted sales in 2011. Among the 24 U.S. states where the death penalty remains legal, only five permit firing squads, with South Carolina now leading its modern application. The three shooters, volunteers from the Department of Corrections, fired from 15 feet away through a slit in the chamber wall, their rifles synchronized after the warden’s command.

Critics decry the method’s brutality, with witnesses noting the bloodshed and visceral impact, while proponents argue it ensures a quicker death than lethal injections, which have caused up to 20-minute agonies in South Carolina since 2021, or the electric chair, last used there in 2008. Sigmon’s execution, completed in under two minutes, contrasted with the state’s average 15-minute lethal injections, fueling discussions about what constitutes “cruel and unusual” punishment under the 8th Amendment.

Legal appeals fall short

Sigmon’s defense, led by attorney Gerald “Bo” King, fought tirelessly to postpone the execution. On March 6, they appealed to the South Carolina Supreme Court, arguing insufficient transparency about the lethal injection drug pentobarbital violated constitutional rights, but the court rejected the plea. A clemency request to Governor McMaster, emphasizing Sigmon’s remorse and Christian faith, was denied hours before the 6 p.m. deadline. A final push to the U.S. Supreme Court also failed, cementing March 7 as the execution date after a 23-year legal battle.

Brutal crime seals death sentence

Sigmon’s conviction stemmed from a savage 2001 crime in Greenville County. Enraged after David and Gladys Larke evicted him from their trailer where he lived rent-free, he stormed their home, beating them to death with a baseball bat in separate rooms. He then kidnapped his ex-girlfriend at gunpoint, firing at her as she fled but missing. A 2002 jury rejected life imprisonment, sentencing him to death for the double murder. Over 23 years on death row at Broad River, where 35 inmates await execution, Sigmon expressed regret, spending hours in prayer, though this failed to sway the courts or governor.

Human rights groups labeled the firing squad “medieval,” but victims’ families, present at the execution, found closure. The case’s brutality underpinned South Carolina’s resolve, despite global condemnation.

Timeline of South Carolina’s death penalty

Key events trace the state’s capital punishment history:

- 1976: U.S. Supreme Court reinstates death penalty after a four-year moratorium.

- 1995: South Carolina conducts its first lethal injection execution.

- 2008: Last electric chair execution in the state.

- 2010: Last U.S. firing squad execution in Utah.

- 2021: Law reinstates firing squad and sets electric chair as default.

- March 7, 2025: Sigmon executed by firing squad.

This timeline highlights the shift in methods, with firing squads reemerging after 15 years.

Execution methods spark controversy

Sigmon’s death intensified scrutiny of U.S. execution practices. Lethal injection, adopted in 1977 as a “humane” alternative to hanging and electrocution, has faced shortages since 2011, prompting states like South Carolina to revive firing squads and electric chairs. Of 1,591 executions since 1976, 1,363 used lethal injection, 163 electrocution, and four firing squads—all in Utah until now. South Carolina’s five executions since 2021 included three lethal injections marred by prolonged suffering reports, pushing the state to alternative methods.

Firing squads, historically tied to military justice and repression, are praised by some for speed—death in seconds if shots hit the heart—but condemned for their gore. The electric chair, operational since 1912 at Broad River and tested in 2024, is shunned by 80% of condemned inmates, per state data, due to its burning effects.

Witnesses describe graphic scene

South Carolina’s firing squad protocol features three shooters with live rounds, unlike Utah’s mix with one blank. Positioned 15 feet from a slit in the chamber wall, they fired at Sigmon, strapped with a target and hood, as 12 witnesses—including media and victims’ kin—watched through bulletproof glass. The shots, following a silent pause, left blood and a chest wound, described as “vivid and bloody” by observers. The $53,000 chamber retrofit in 2022 ensured precision, but the visceral aftermath stunned attendees.

Sigmon’s final meal of fried chicken and sides, served the previous day, preceded a swift execution lasting under three minutes, with his last sighs echoing in the chamber.

Other states eye firing squads

Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah also permit firing squads, while Idaho approved them in 2025 as a fallback if lethal injections fail. Of 35 U.S. executions in 2024, 90% used lethal injection, but dwindling pentobarbital stocks spurred alternatives like nitrogen hypoxia, debuted in Alabama, and firing squads. South Carolina defaults to the electric chair since 2021, but Sigmon’s choice highlighted firing squads’ resurgence, driven by his rejection of other methods’ perceived cruelty.

This shift reflects a broader impasse: with 24 states retaining the death penalty, finding effective, legal methods remains divisive, though 60% of Americans back it for murder, per 2024 polls.

Global outcry follows execution

Sigmon’s execution, South Carolina’s fifth since 2021, sparked international backlash, with human rights groups branding firing squads “barbaric.” Of 50 countries with capital punishment, 20 use firing squads, including Indonesia, which executed two Brazilians in 2015. In the U.S., the method’s rarity contrasts with Sigmon’s choice, rooted in fears of prolonged suffering from electrocution or injection. South Carolina’s 44 executions since 1976 cost an average of $70,000 each, with Sigmon’s requiring $53,000 in chamber upgrades.

His death, marked by muffled final words under a hood, leaves a legacy in U.S. capital punishment history as the 35 remaining death row inmates in the state await their fates.